The Birth of the Indonesian Nation, 1945 – 1949: Perspectives on the Role of the United States

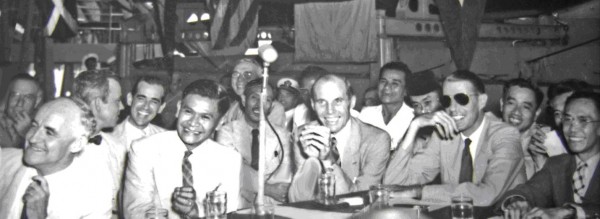

As part of USINDO’s effort to communicate the history of US-Indonesia relations to a new generation, on June 6th, USINDO’s Jakarta office, in cooperation with The Indonesian Heritage Society, held a Special Event featuring Professor Ron Spector, a military historian from George Washington University, before a large audience.

Spector reviewed the US position on colonialism and foreign involvement, to set the scene for the US position toward Indonesia’s independence from the Dutch between 1945 and 1949.

American leaders have usually described America as anti-colonial, originating in their own fight for independence from the British. For example, the Monroe Doctrine’s policy was that the Europeans cannot extend their system to the New World.

America has had recurrent periods of isolationism as well, starting with President Washington’s farewell address which emphasized that there shall be no need for entangling alliances; he said “in extending our commercial relations let us have as little political connection as possible.”

Yet America also has often been sympathetic toward the freedom of nations. John Quincy Adams said: “Wherever the standard of freedom and independence has been or shall be unfurled there will her heart, her prayers and her benedictions be. But she goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all nations. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own.” July 4, 1821.

The US did practice colonialism as well, of course, such as acquiring the Philippines in 1898. However, the U.S. came to be divided about this, reflecting a conflicted attitude regarding colonialism. During the first half of the 20th century, Americans debated if colonialism was wrong, or necessary to help Southeast Asians learn to govern themselves, the view of many.

In the aftermath of the Alliance victory in the Europe and the Japanese flight from Southeast Asia, the US was conflicted. The US originally supported the European occupation of the region. However, as the WWII was ending, the US began to grow weary of the European powers and their colonies. A common joke that reflected the sentiment at the time was that SEAC – the Southeast Asia Command – meant as ‘Save England and Its Asian Colonies.’

Prior to 1947, the US’s policy toward Indonesia’s independence could be described as ‘benign indifference.’ The U.S. in those years was much more concerned with Dutch economic recovery in Europe than with the status of Dutch colonies.

Then, with the Dutch “Police Action” in the Netherlands East Indies of July 1947, tensions began to rise between the US and other countries that acknowledged Indonesia’s independence, such as Australia and India.

In August 1947, the US agreed to serve as head of the United Nations’ “Committee of Good Offices” (GOC) (created under the UN Commission for Indonesia), with an initial policy that “the Dutch should retain considerable stake in the Netherlands East Indies.”

As the head of the Good Offices Committee, the US played a significant role in serving as a mediator among the new Republic and the Dutch. The US was instrumental in establishing the Renville Agreement of January 1948 which instituted a cease-fire in hostilities.

Following the Renville Agreement, GOC officers became disillusioned with the Dutch military and more sympathetic to the Republic’s side which they dubbed as “reasonable.”

One turning point of US attitudes toward Indonesia was the “Madiun Affair” of September 1948. The communist uprising in the town of Madiun in East Java gave the new leaders of the nascent Republic a chance to prove to the US their willingness and ability to quash communist influence. For the US, this rebellion was the final confirmation of Indonesia’s ability to be independent.

Then, in December 1948, Operation Crow, a Dutch attack on Yogyakarta, caused strong negative reactions by the US and the GOC, and the realization that the Dutch could not win the drawn out hostilities. A hostile international reaction followed quickly, and the US used the opportunity to pressure the Dutch to give Indonesia independence.

The final decision was reached when the US threatened to withhold from the Netherlands Marshall Plan Aid intended to help rebuild Europe following WWII, if the Dutch did not consent to the independence of Indonesia.

Thus, U.S. policies played a key role in the Dutch transfer of sovereignty to the new Republic of Indonesia on December 27, 1949.